Co-morbidity of Eating Disorders and Substance Abuse Review of the Literature

- Review

- Open up Access

- Published:

The prevalence of substance use disorders and substance use in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Journal of Eating Disorders book 9, Article number:161 (2021) Cite this article

Abstract

Aim

Individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) often present with substance use and substance employ disorders (SUDs). However, the prevalence of substance use and SUDs in AN has not been studied in-depth, especially the differences in the prevalence of SUDs betwixt AN types [e.one thousand., AN-R (restrictive blazon) and AN-BP (binge-eating/purge type]. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to appraise the prevalence of SUDs and substance use in AN samples.

Method

Systematic database searches of the peer-reviewed literature were conducted in the following online databases: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and CINAHL from inception to Jan 2021. We restricted review eligibility to peer-reviewed research studies reporting the prevalence for either SUDs or substance use in individuals with AN. Random-effects meta-analyses using Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformations were performed on eligible studies to estimate pooled proportions and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Fifty-two studies met the inclusion criteria, including 14,695 individuals identified equally having AN (hateful age: 22.82 years). Random pooled estimates showed that substance utilise disorders had a 16% prevalence in those with AN (AN-BP = 18% vs. AN-R = 7%). Drug abuse/dependence disorders had a prevalence of seven% in AN (AN-BP = nine% vs. AN-R = v%). In studies that looked at specific abuse/dependence disorders, at that place was a 10% prevalence of booze abuse/dependence in AN (AN-BP = 15% vs. AN-R = 3%) and a 6% prevalence of cannabis abuse/dependence (AN-BP = iv% vs. AN-R = 0%). In improver, in terms of substance use, there was a 37% prevalence for caffeine use, 29% prevalence for alcohol apply, 25% for tobacco use, and 14% for cannabis use in individuals with AN.

Conclusion

This is the most comprehensive meta-analysis on the comorbid prevalence of SUDs and substance utilize in persons with AN, with an overall pooled prevalence of 16%. Comorbid SUDs, including drugs, booze, and cannabis, were all more common in AN-BP compared to AN-R throughout. Therefore, clinicians should exist aware of the loftier prevalence of SUD comorbidity and substance use in individuals with AN. Finally, clinicians should consider screening for SUDs and integrating treatments that target SUDs in individuals with AN.

Plain English language Summary

Individuals with anorexia nervosa (AN) may also present with substance employ or take a substance use disorder (SUDs). Thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to make up one's mind the prevalence of substance apply and substance use disorders in individuals with AN. Nosotros examined published studies that reported the prevalence of either substance use or SUDs in individuals with AN. We establish that substance use disorders had a 16% prevalence and that drug abuse/dependence disorders had a prevalence of 7% in those with AN. These rates were much college in individuals with rampage-eating/purging type compared to the restrictive AN. However, many specific substance use disorders and substance use types were low in individuals with AN. Nonetheless, clinicians should be enlightened of the high prevalence of SUD comorbidity and substance utilise in individuals with AN.

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are associated with a series of comorbidities, including depression, feet, personality disorders, and substance employ disorders (SUDs) [29]. A recently published meta-analysis on the prevalence rates examining the comorbidity of SUDs in EDs constitute that the pooled prevalence of SUDs in EDs was 22% [6], with the prevalence of EDs among individuals seeking treatment for SUDs being 35%. Thus, the prevalence of EDs in individuals with SUDs appears to be ten times college than the prevalence of EDs in the full general population [21], with the prevalence of SUDs among individuals with EDs in treatment betwixt 25 and 50% [22, 57].

Research shows weaker associations between restrictive types of EDs [e.g., Anorexia Nervosa (AN)] and SUDs, although mechanisms of habit may also be at play in AN [26, 44, threescore, 61]. For case, cues such equally pictures of underweight bodies or physical activities are reinforcers and are associated with activation/sensitization of brain structures of reward [24, 27], while other cues such as pictures of loftier-calorie foods practice not get along with approach reactions [45]. Such findings have led to the "reward-centered" model, which posits that food cues are processed as aversive, just disorder-compatible signals are candy positively and activate the mesolimbic reward system [44]. Afterward, restrictive eating behaviors and disorder-compatible behaviors in AN (eastward.g., fasting, concrete activeness, frequent weighing, etc.) larn the character of automated habitual behaviors and may atomic number 82 to maintenance of the disorder. Thus, comparable to addictive disorders, a transition from goal-directed to automatic habitual behaviors in response to disorder-compatible stimuli may be at play. In improver, innovative treatment approaches (such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and deep-brain stimulation), targeting brain action associated with the regulation of both food and addictive substance intake, appear to be emerging and to show promising results [xvi, 28, 48, 49], which may aid with the reduction of symptoms in both AN and SUDs.

Overall, despite prove demonstrating similarities in the underlying mechanisms, associations, and prevalence of AN and SUDs, SUD in AN have not been studied in-depth in a systematic review and meta-analysis. In add-on, information on the prevalence of substance use (at whatsoever frequency) in AN may help contextualize the specific patterns of substances that are more likely to lead to functional consequences in persons with AN. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to: (1) appraise the prevalence rates of comorbidities betwixt AN and SUDs or substance utilize (2) assess the prevalence of SUDs and substance use by AN type (AN-R and AN-BP); and (three) appraise the quality of peer-reviewed literature to date. This is necessary to understand AN comorbidities, clinical indicators, and outcomes and inform time to come treatment planning.

Method

Protocol and guidelines

This systematic review and meta-assay were prospectively registered with PROSPERO and adhered to both PRISMA (preferred reporting for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and MOOSE (meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology) recommendations [34, 39, 56].

Systematic search strategy

Systematic searches of the peer-reviewed literature was conducted following PRESS guidelines [47] in consultation with a medical librarian in 4 electronic databases (i.eastward., MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase, and CINAHL) from inception to October 13th, 2021. The key words included ii concepts: (1) anorexia nervosa (AN) and (2) substance Employ or substance use disorder terms. Database searches and an exhaustive listing of key terms are provided in the Boosted file i: search material. Two blinded reviewers performed championship/abstruse screening (A.A. and J.F.) and full-text article screening (A.A. and A.S.) in duplicate. In addition, reference lists of included articles were paw-searched for other relevant studies.

Report selection criteria

Two reviewers selected peer-reviewed articles (A.A. and A.S.) for inclusion in this systematic review based on the post-obit criteria: (1) research including participants with anorexia nervosa (AN), restrictive AN (AN-R), and AN of the binge-eating/purging type (AN-BP); and (2) reported on the prevalence of either substance use (e.g., alcohol employ, tobacco use, cannabis use), substance use disorders, or drug abuse/misuse/dependence disorders. In addition, this review excluded studies that: (1) looked at the relationship between AN and other behavioral addictions (e.g., gambling disorder) or impulse control disorders, (2) study designs that were case reports, review articles, opinion pieces, and editorials, (three) studies that included use/abuse of prescribed medications and (iv) did not study sufficient information to summate a prevalence rate. Disagreements were first discussed in a consensus coming together, and D.D. decided on inclusion or exclusion.

Information extraction

Data extraction for Table one was completed in duplication (A.A. and One thousand.P.), including the post-obit study and participant characteristics: author, year of publication, land, study blazon, types of substance utilize/abuse/dependence, AN types, age (mean ± SD), percent female (number of females), and outcomes reported. For the meta-analysis, the following information were extracted in duplicate (A.A. and D.D.): (1) writer, (2) year of publication, (3) types of substance use, substance abuse/dependence disorders, and drug abuse/dependence disorders, (4) AN type, (5) numerator representing substance utilise/abuse/dependence disorders, and drug corruption/dependence disorders, (half-dozen) denominator representing AN sample, and (7) lifetime prevalence or flow prevalence.

Risk-of-bias cess

Studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were assessed for quality using a modified Downs and Black instrument [19] which contains fourteen-items for cross-sectional studies, providing a total score of fifteen for each study indicating greater quality. Scores of ≥ 11.five (> 75%), 9–eleven (60–74%), and < ix (< 60%) were taken to indicate high, moderate, and depression quality, respectively.

Data synthesis and analysis

Due to potential heterogeneity between studies, successions of DerSimonian and Laird [18] random-effects meta-analyses were performed on eligible studies to estimate the pooled prevalence and 95% CIs for substance apply disorders, drug abuse/misuse/dependence disorders, and substance use. The primary issue measure out was total substance use disorders and the summary statistic used in the meta-analysis was the pooled prevalence. Many studies distinguish total substance utilise disorders from total drug abuse/dependence disorders past not including alcohol in the drug corruption/dependence disorder count. Thus, these two concepts were kept split up in the meta-analysis. In improver, differences in the pooled prevalence between AN-R and AN-BP were examined. All meta-analyses in this newspaper employed Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformations, with the verbal confidence interval method, by computing the weighted pooled approximate and so performing a back-transformation on the pooled estimate. This arroyo is favorable where there is zero count prevalence equally information technology prevents these studies from being dropped from the meta-analysis, which would create a bias in prevalence estimates. Lifetime prevalence and catamenia prevalence were showtime examined separately, only at that place was minimal variation between the ii prevalence types. Thus, we combined the two (eastward.g., some studies reported lifetime and other studies reported period prevalence, both types were included in the same meta-assay) to provide an overall prevalence for each outcome. Two studies was the minimum amount of studies included in each pooled meta-analysis. However, prevalence was also presented when reported by just one written report, yet this is not an estimate derived from a meta-analysis. Statistical heterogeneity was examined using the I2 statistics, an Itwo value is just produced for a meta-analysis with four or more studies in the meta-analysis. Nosotros performed all analyses in STATA v.17 [54] and produced wood plots showing the prevalence of those with either substance use disorders or drug corruption/dependence disorders in those with AN.

Results

Search yield

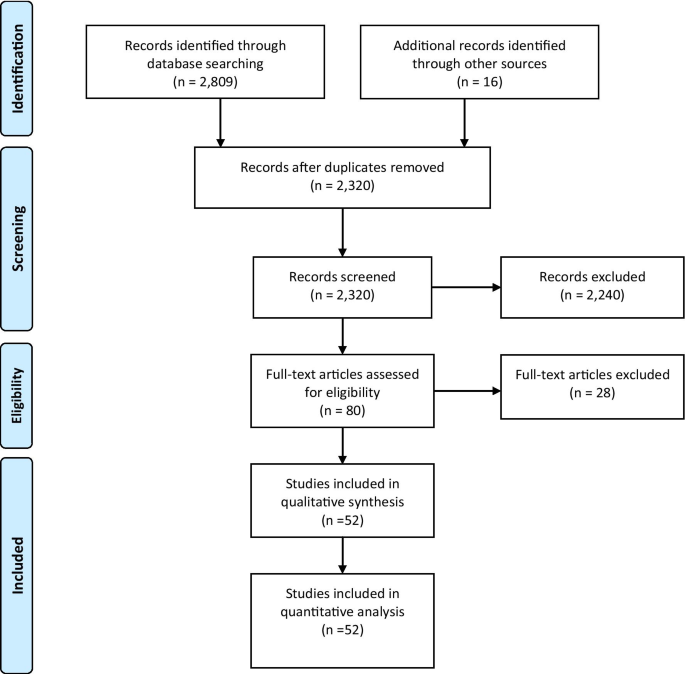

Database searches returned 2809 abstracts and titles. After duplicate references were removed, 2320 abstracts and titles were screened. The level of agreement betwixt two blinded reviewers for screening was moderate (κ = 0.65). After resolution of discrepancies, eighty total-text studies were retrieved and reviewed independently, of which a full of 52 studies met the inclusion criteria for this review (run across Fig. 1). In total, 35 studies measured SUDs, 17 measured substance apply, with six of these studies measuring both SUDs and substance use.

PRISMA menstruation diagram

Participant characteristics and study characteristics

In that location was a total fourteen,695 individuals identified as having AN included in this review, ranging from sample sizes of xv to 8069 for individuals with AN in split studies, Tabular array 1. The hateful age of individuals with AN was 22.82 years (Range 14.iii–35.0), and the percentage of females was 95.half-dozen%.

Studies were published between 1983 and 2019. Well-nigh studies were conducted in Northward America (n = 26), followed past Europe (n = sixteen), Asia (n = 6), and New Zealand (n = 4). Xx-ii studies included a comparison or control group in their corresponding written report. 40-two studies identified individuals with AN from a infirmary setting (9 = outpatient, vii = inpatient), ED programs, or specialized dispensary, with six studies identifying AN individuals from research studies. Additional file ane: Table S2 describes in greater detail outcomes reported in each report, including subgroup analyses, comparing groups, sex differences, and other relevant information related to AN and SUDs or substance use outcomes.

Quality assessment of included studies

All studies included in this systematic review were evaluated with the modified Downs and Blackness instrument (Boosted file one: Table S1). The boilerplate Downs and Black score was x.9/fifteen, demonstrating mostly moderate quality across studies. The majority of studies clearly described their chief aims, measures, and findings. Nevertheless, well-nigh studies included in this review failed to account for the effects of meaning covariates.

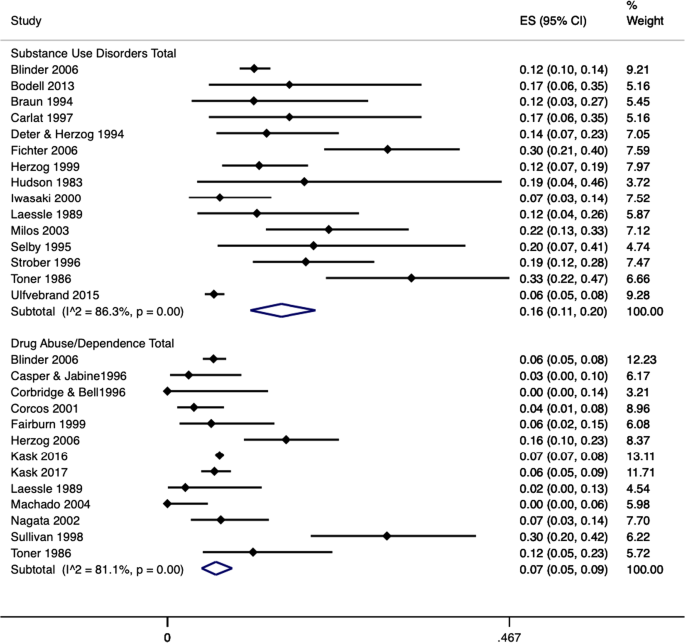

Prevalence of substance use disorders and drug corruption/dependence

In studies that looked at total substance apply disorders, random pooled estimates demonstrated that substance use disorders had a xvi% prevalence in those with AN (95% CI = 0.11–0.20; Iii = 86.3%; 15 studies, N = 3118), see Fig. 2. Individuals with AN-BP had a higher prevalence of substance employ disorders at 18% (95% CI = 0.12–0.26; Itwo = 82.ane%; 6 studies, Due north = 1058) compared to 7% in those with AN-R (95% CI = 0.04–0.10; Iii = 69.three%; 8 studies, Northward = 1635), encounter Boosted file 1: Figure S1.

Woods plot of the prevalence of substance utilise disorders and drug abuse/dependence disorders in AN. Notes: Blue diamond represents the overall pooled event per outcome, ES = event size

Drug abuse/dependence disorders had a prevalence of 7% in AN (95% CI = 0.05–0.09; I2 = 81.i%; 13 studies, N = 10,443), with individuals with AN-BP having a higher prevalence of drug corruption/dependence at 9% (95% CI = 0.03–0.17; Itwo = 65.eight%; five studies, North = 235) compared to 5% in those with AN-R (95% CI = 0.02–0.09;; I2 = 35.viii%; 5 studies, Due north = 278), see Additional file 1: figure S2.

Prevalence of specific substance employ disorders

In studies that looked at specific substance apply disorders, random pooled estimates demonstrated that there was a 10% prevalence of alcohol corruption/dependence in AN (15% AN-BP vs. 3% AN-R), 6% prevalence of cannabis abuse/dependence in AN (4% AN-BP vs. 0% AN-R), and a 5% prevalence of amphetamine corruption/dependence in AN. Even so, the bulk of specific substance use disorders identified in this review remained low comparatively. Prevalence estimates for other specific forms of substance corruption/dependence are provided in Table 2.

Prevalence of substance employ

There was a 20% prevalence for substance use (95% CI = 0.08–0.34; I2 = 94.27; four studies, N = 769) in studies that looked at substance use total in individuals with AN. In studies that looked at types of substance use in individuals with AN, there was a 37% prevalence for caffeine (95% CI = 0.08–0.73; iii studies, N = 107), followed past a 29% prevalence for alcohol (95% CI = 0.22–0.36; I2 = 70.56; 5 studies, N = 677), 25% for tobacco (95% CI = 0.16–0.34; Iii = 90.65; 9 studies, N = 1352), 14% for cannabis (95% CI = 0.03–0.28; Iii = 95.18; 5 studies, Due north = 720), and 14% stimulants use (95% CI = 0.11–0.18; 2 studies, Northward = 383). However, the majority of specific substance apply identified in this review remained low insufficiently. Prevalence estimates for other forms of substance use are provided in Table 3.

Give-and-take

Summary of findings

The present meta-analysis evaluated the prevalence of co-occurring substance use and substance use disorders (SUD) among persons with anorexia nervosa (AN). In total, 52 studies met review eligibility criteria. The overall prevalence of substance use of any kind was 20%, including caffeine (37%), booze (29%), tobacco (25%), cannabis (14%), and stimulants (14%). The overall prevalence of whatsoever SUD was sixteen%, including drug abuse/dependence (7%), alcohol (10%), cannabis (6%), and amphetamines (5%). Globally, the prevalence of drug utilise disorders among the population anile 15–64 is estimated to exist 0.71% (Drugs & Crime, 2019), thus the prevalence in AN appears to be high comparatively. The sample included in this meta-analysis was predominantly female, however, when looking at studies that included only males in the electric current review, males had an estimated prevalence of 17% for SUD full, 6% for drug abuse/dependence, and between a eight–13% prevalence for booze abuse/dependence, which appears to be similar to females but based on very few studies. The overall sample was likewise younger in this meta-analysis with a mean age of 23, and potentially overtime the prevalence of these disorders may increase. Substance employ and SUD prevalence were college among people with the rampage-eating/purge (AN-BP) blazon than those with the restrictive (AN-R) type throughout. Nonetheless, the bulk of SUDs and substance use announced to be very depression or not present in AN patients including allaying apply, hallucinogen use, opioids, and inhalants.

Handling implications

The high prevalence of comorbid substance use and SUD in persons with AN has important treatment implications. SUD direction in the absenteeism of ED comorbidity begins with a thorough psychiatric interview for diagnostic evaluation and treatment planning [35]. Stress and trauma are etiological factors in both SUD and ED, and diagnostic interviews must consider these aspects [12]. Treatments for ED and SUD are individualized, substance- or ED-specific, and mindful of an private's intrinsic motivation and readiness for change [62]. For SUD, individuals identify forbearance or damage reduction goals; the latter refers to continued substance use instead of incrementally using less to mitigate risk [31]. With these general frameworks in mind, the next component of treatment is usually tailored towards the specific ED-SUD combination. A variety of psychotherapeutic, psychosocial, and fifty-fifty pharmacological therapies are bachelor for ED and SUD, only few studies have explored treatments for co-occurring disorders [6]. At present, clinicians generally pick treatments that could piece of work synergistically, as some therapies have indications for both diseases. For alcohol use disorder (AUD), the three first-line medications are naltrexone (an opioid receptor antagonist blocking the endogenous reward associated with booze consumption), disulfiram (an inhibitor of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, causing a toxic reaction if alcohol is consumed due to accumulation of booze metabolites), and acamprosate (an NMDA receptor adversary that reduces cravings for alcohol). For opioid utilize disorder (OUD), offset-line pharmacotherapies include methadone and buprenorphine, synthetic opioids that suppress opioid withdrawal and cravings [4, 32]. For tobacco use disorder (TUD), nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline (a partial agonist of the acetylcholinergic receptor), and bupropion (a noradrenergic-dopaminergic antidepressant) are testify-based treatments that can improve quit rates and sustained abstinence from tobacco [37]. While the DSM-5 does not currently recognize caffeine use disorder, caffeine withdrawal and intoxication are formal diagnoses [1]. More often than not, it is possible that treatments for co-occurring SUD in people with AN may non interfere with AN handling.

Given the high degree of comorbidity between SUDs and AN, it is essential to develop treatment strategies that are constructive for both weather. Pharmacologically, most medications used to treat AN or to treat SUD are compatible with i another. For example, the use of opioid agonist therapies for opioid apply disorder and naltrexone or acamprosate for alcohol use disorder could complement the pharmacological treatment. Withal, equally some of these medications for SUDs can prolong the QTc interval, they raise the risk of new-onset cardiac arrhythmias, which may be more likely in persons with AN who are very underweight and if they have electrolyte abnormalities. At that place are currently no canonical pharmacological interventions for stimulant, cannabis [five, 7], or hallucinogen use disorders. For cannabis utilize disorder (CUD), the occurrence of cannabis withdrawal and intoxication can also induce anorexia symptoms, nausea, airsickness, and weight loss and tin can occur in nigh half of persons with CUD [8]. For CUD, in that location are no approved pharmacotherapies, and the only treatment with electric current efficacy for withdrawal symptoms is sustained forbearance.

Nonetheless, several psychosocial interventions have evidence for both ED and co-occurring SUD, such as self-help approaches [59], mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy [15], dialectical behavioral therapy [14], family and couples therapy [42], and contingency management [20]. While there are several reasons why some psychosocial interventions may demonstrate efficacy for co-occurring AN and SUD, one reason might exist transdiagnostic psychopathology that responds to the same types of treatments [36]. For case, Claudat et al. fabricated a case for the effectiveness of DBT for persons with co-occurring EDs and SUD every bit such persons share difficulties with emotion regulation, goal-directed activity, and impulsivity [14].

New and innovative interventions such as existent-fourth dimension fMRI-based neurofeedback, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcranial straight electric current stimulation, and deep brain stimulation aim to influence brain regions' activity to regulate food and addictive substance intake [17]. These interventions follow the assumption that in that location are two circuits in the brain controlling both food intake in EDs and substance use in SUDs; the first excursion responds to salient/rewarding stimuli and consists of structures like ventral striatum, amygdala, anterior insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex/orbitofrontal cortex. The second excursion regulates the degree of cognitive command over food or addictive substance intake and includes brain structures such every bit the inductive cingulum and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex [58]. Thus, future research in the grade of randomized control trials are needed to test the variety of handling strategies mentioned above in an effort to reduce symptoms in individuals suffering from comorbid SUDs and AN.

Overlapping features between SUDs and AN

Although SUD and AN potentially appear to respond to some of the same treatments, these disorders are distinct. However, both conditions are behaviourally defined psychiatric disorders [46] and may also accept some genetic overlap [41]. For SUD, aberrations in the endogenous reward system drive pathological craving and drug-seeking behaviors, leading to a continued cycle of intoxication and withdrawal [2]. For AN, a negative view of one'due south torso epitome drives caloric brake, low BMI, and for some, repeated compensatory behaviors to maintain low body weight, such every bit purging, extreme exercise, laxative use, and fasting, often associated with subjective and objective binge episodes [1]. Several working hypotheses have been put forwards as potential explanations for their overlap as these two disorders commonly co-occur [25]. The offset hypothesis involves self-regulation through self-medication, which means that substance utilise and AN behavior (e.g., brake, rampage behaviors, purging) are used to "care for" an underlying pathology [30, 52]. Frequently, persons with SUD and AN both describe a chaotic inner milieu that temporarily abates from the effects of substances or caloric restriction [9]. The second hypothesis assumes shared risk factors or underlying causes. For case, a bulldoze towards perfectionism, impulsivity, novelty-seeking, and rigidity/obsessions announced to raise the risk for the development of both ED and SUD [38, 53]. One of our review's findings -that the prevalence of substance apply and SUD was college in AN-BP compared to AN-R- appears to back up this second hypothesis, as AN-BP has more features consistent with the impulsive, novelty-seeking phenotype seen in persons with SUD [11, 43, 50]. Finally, specific substances may appear to serve a functional purpose for forms of ED. In the setting of ED, appetite-suppressing substances, such as tobacco, may help maintain a low appetite [3, 40]. In improver, caffeine and stimulants may also suppress appetite, maintain caloric restriction, fuel intense practise, and address fatigue stemming from macerated BMI [10, 55]. Alcohol may lessen the severity of AN-induced anxiety and melancholia symptoms [xiii] and may increase ambition [51].

Recent neurobiological findings support the notion that mechanisms of addiction may as well be involved in the development and maintenance of AN [44, 61]. On the one hand, high-calorie food cues, which may be considered "incompatible" with AN, are processed with anxiety and associated with increased activation of brain regions responsible for inhibitory control [61], which is per abstention bias regarding food constitute in individuals with AN [45]. On the other paw, disorder-compatible stimuli (eastward.g., images of underweight women's bodies, physical activeness cues) are appetitively processed; such sensitization processes of the advantage system may lead to maintaining the problematic behavior patterns seen in AN. For instance, females with AN instructed to imagine that their own body would stand for to specific normal-weight or underweight body cues showed more robust activation in structures of the reward system, particularly in the ventral striatum, during the self-referential processing of images of underweight bodies compared with normal-weight bodies; the opposite pattern was found for healthy female subjects [23]. Similar results were shown using other techniques as well: both EEG and eye-tracking studies, besides as studies in which the blink reflex was recorded as a measure of appetitive valence, have revealed an attentional bias/positive processing for images of underweight female person bodies and images of physical activity [27], comparable to the processing of alcohol-associated stimuli in alcohol-dependent patients. Accordingly, O'Hara and colleagues [44] postulated a "reward-centered" model of AN, which assumes that food-associated stimuli are experienced as aversive.

In contrast, disorder-compatible stimuli (such as underweight body images and concrete activity) are processed positively and activate the mesolimbic reward organisation. Likewise, individuals with AN exhibit greater activation in prefrontal brain areas, somatosensory cortex, and cerebellum when responses to concrete activeness stimuli are to be inhibited in a go-no-become chore [33]. This also corresponds to findings regarding the neuronal activation patterns of alcohol-dependent patients during response inhibition towards alcohol-associated stimuli. Such findings advise an inhibition deficit for disorder-uniform rewarding behaviors.

Strengths and limitations

The present meta-analysis has several strengths. The robust methods and adherence to Printing, PRISMA, and MOOSE guidelines are one, while the large yield of studies (due north = 52) and participants (northward = 14,695 individuals identified as having AN) were others. In add-on, the studies included in this meta-analysis were of off-white to moderate quality. The review likewise advances the field by focusing on the prevalence of both substance utilise and SUD in persons with AN. While a previous review by Bahji et al. found similar SUD prevalence estimates in EDs [6], the present report identified more studies. While having SUD estimates provides a meaningful assessment of clinically significant impairment, the boosted information provided by substance use helps contextualize the specific patterns of substances that are more likely to lead to functional consequences in persons with AN.

Withal, there are a few limitations. First, as a meta-analysis of prevalence, we encountered high heterogeneity when pooling estimates across studies. Some of this heterogeneity occurred from combining the different types of AN, and stratification into AN-BP and AN-R-specific estimates helped reduce some heterogeneity. Withal, at that place are other potential sources of heterogeneity that we did not explore analytically due to the express number of studies per subgroup analysis. For case, variations in substance use and SUD measurements across studies likely increased heterogeneity due to different ascertainment methods (east.k., self-study, informant-report, structured interviews, urine drug screens) and alternative diagnostic criteria (e.g., DSM-Three, DSM-IV, and DSM-5). In addition, many specific substance use disorders and different types of substance employ had a very low prevalence in those with AN, even so this may be due to the limited amount of studies bachelor for these outcomes. Specifically, many of the substance use prevalence rates were much lower than the general populations, such as alcohol apply and caffeine utilise. The generalizability of the results is another limitation, as nearly participants were immature women; consequently, our review's findings are less applicable to males in general and older populations. Finally, we cannot make up one's mind causal relationships betwixt substance use, SUD, and AN every bit an observational review.

Conclusions

This is the nearly comprehensive meta-assay on the comorbid prevalence of SUDs and substance utilise in persons with AN, with an overall pooled prevalence of 16%. Comorbid SUDs were much more common in AN-BP compared to AN-R. Clinicians should be aware of the high prevalence of specific SUD comorbidity and substance use in individuals with AN. Finally, clinicians should consider screening for SUDs and integrating treatments that target SUDs in individuals with AN.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AN-R:

-

Anorexia nervosa-restricting type

- AN-P:

-

Anorexia nervosa-purging type

- AN-B:

-

Anorexia nervosa-binging type

- ANBN:

-

Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa

- ED:

-

Eating disorder

- AN-BP:

-

Anorexia nervosa, binge-eating/purging type

- BN:

-

Bulimia nervosa

- MDD:

-

Major depressive disorder

- AUD:

-

Booze use disorder

- DUD:

-

Drug use disorder

- SUG:

-

Substance use group

- NSUG:

-

No substance use group

References

-

American Psychiatric Clan. DSM-V: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition. (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Clan (2013). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

-

American Society of Addiction, Chiliad. Definition of Addiction (2021). Retrieved 2021/06/11/20:32:31 from https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/public-policy-statements/1definition_of_addiction_long_4-xi.pdf?sfvrsn=a8f64512_4

-

Anzengruber D, Klump KL, Thornton 50, Brandt H, Crawford South, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Johnson C, Kaplan Every bit, LaVia M, Mitchell J, Strober M, Woodside DB, Rotondo A, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH, Bulik CM. Smoking in eating disorders. Eating Behav. 2006;vii(4):291–nine. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.06.005.

-

Bahji A, Bajaj Due north. Opioids on trial: a systematic review of interventions for the handling and prevention of opioid overdose. Can J Addic. 2018; 9(i). https://journals.lww.com/cja/Fulltext/2018/03000/Opioids_on_Trial__A_Systematic_Review_of.4.aspx

-

Bahji A, Mazhar MN. Treatment of Cannabis dependence with synthetic cannabinoids: a systematic review. Tin can J Addic. 2016; 7(iv). https://journals.lww.com/cja/Fulltext/2016/12000/Treatment_of_Cannabis_Dependence_with_Synthetic.3.aspx

-

Bahji A, Mazhar MN, Hudson CC, Nadkarni P, MacNeil BA, Hawken East. Prevalence of substance use disorder comorbidity among individuals with eating disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:58–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.007.

-

Bahji A, Meyyappan AC, Hawken ER, Tibbo PG. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis use disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;97, 103295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103295

-

Bahji A, Stephenson C, Tyo R, Hawken ER, Seitz DP. Prevalence of cannabis withdrawal symptoms amid people with regular or dependent use of cannabinoids. JAMA Netw Open up. 2020;3(4), e202370. https://doi.org/ten.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2370

-

Barbarich-Marsteller NC, Foltin RW, Walsh BT. Does anorexia nervosa resemble an addiction? Curr Drug Abuse Rev. 2011;4(three):197–200.

-

Berardisa DD, Matarazzo I, Orsolini L, Aless VR, Tomasetti C, Montemitro C, Mazza M, Fornaro M, Carano R, Perna G, Vellante F, Sante DD, Rovere RL, Martinotti Grand, Trotta S, Giannantonio Md. The trouble of eating disorders and comorbid psychostimulants abuse: a mini review. 2019;9(three):2359–2368. https://www.jneuropsychiatry.org/peer-review/the-trouble-of-eating-disorders-and-comorbid-psychostimulants-abuse-a-mini-review.pdf

-

Bollen Eastward, Wojciechowski FL. Anorexia nervosa subtypes and the big 5 personality factors. Eur Eating Disord Rev. 2004;12(2):117–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.551.

-

Brewerton TD, Brady One thousand. The role of stress, trauma, and PTSD in the etiology and treatment of eating disorders, addictions, and substance utilise disorders. In: Brewerton TD, Baker Dennis A, Brewerton TD, Baker Dennis A (eds), Eating disorders, addictions and substance use disorders: research, clinical and treatment perspectives, pp. 379–404 (2014). https://doi.org/x.1007/978-3-642-45378-6_17

-

Bulik CM, Klump KL, Thornton Fifty, Kaplan Equally, Devlin B, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Strober M, Woodside DB, Crow S, Mitchell JE, Rotondo A, Mauri M, Cassano GB, Keel PK, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH. Alcohol utilize disorder comorbidity in eating disorders: a multicenter study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):1000–vi.

-

Claudat Yard, Chocolate-brown TA, Anderson L, Bongiorno G, Berner LA, Reilly Due east, Luo T, Orloff N, Kaye WH. Correlates of co-occurring eating disorders and substance employ disorders: a case for dialectical behavior therapy. Eat Disord. 2020;28(2):142–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1740913.

-

Courbasson CM, Nishikawa Y, Shapira LB. Mindfulness-action based cognitive behavioral therapy for concurrent binge eating disorder and substance use disorders. Eat Disord. 2010;xix(i):17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2011.533603.

-

Dalton B, Bartholdy S, Campbell IC, Schmidt U. Neurostimulation in clinical and sub-clinical eating disorders: a systematic update of the literature. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2018;16(eight):1174–92. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X16666180108111532.

-

Dalton B, Campbell IC, Schmidt U. Neuromodulation and neurofeedback treatments in eating disorders and obesity. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2017;30(half-dozen):458–73.

-

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controll Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88. https://doi.org/ten.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

-

Downs SH, Black Due north. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the cess of the methodological quality both of randomised and not-randomised studies of health intendance interventions. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 1998;52(half-dozen):377–84. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.52.half dozen.377.

-

Dutra Fifty, Stathopoulou 1000, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, Otto MW. A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):179–87. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111851.

-

Elmquist JA, Shorey RC, Anderson SE, Temple JR, Stuart GL. The human relationship betwixt eating disorder symptoms and treatment rejection amongst immature adult men in residential substance use treatment. Substance Corruption Res Care for. 2016;10:39–44.

-

Fassino S, Pierò A, Tomba East, Abbate-Daga G. Factors associated with dropout from treatment for eating disorders: a comprehensive literature review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009; 9.

-

Fladung A-K, Grön G, Grammer K, Herrnberger B, Schilly E, Grasteit S, Wolf RC, Walter H, Von Wietersheim J. A neural signature of anorexia nervosa in the ventral striatal reward system. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):206–12. https://doi.org/ten.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010071.

-

Fladung AK, Schulze UME, Schöll F, Bauer K, Grön G. Function of the ventral striatum in developing anorexia nervosa. Transl Psychiatry. 2013;3(10):e315.

-

Fouladi F, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Engel SG, Crow Due south, Hill L, Le Grange D, Powers P, Steffen KJ. Prevalence of booze and other substance use in patients with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev J Eat Disord Assoc. 2015;23(6):531–6. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2410.

-

Godier LR, Park RJ. Compulsivity in anorexia nervosa: a transdiagnostic concept. Front Psychol. 2014;5:778.

-

Horndasch Due south, Kratz O, Van Doren J, Graap H, Kramer R, Moll GH, Heinrich H. Cue reactivity towards bodies in anorexia nervosa - Common and differential effects in adolescents and adults. Psychol Med. 2018;48(3):508–eighteen.

-

Jansen JM, Daams JG, Koeter MWJ, Veltman DJ, van den Brink W, Goudriaan AE. Effects of non-invasive neurostimulation on craving: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(x, Part 2):2472–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.009.

-

Keski-Rahkonen A, Mustelin L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(half-dozen):340–v. https://doi.org/ten.1097/yco.0000000000000278.

-

Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harvard Rev Psychiatry. 1997;four(5):231–44. https://doi.org/10.3109/10673229709030550.

-

Kleber, H. D. et al. Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatric Clan. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(4 Suppl): 5–123.

-

Korownyk C, Perry D, Ton J, Kolber MR, Garrison Southward, Thomas B, Allan GM, Dugré N, Finley CR, Ting R, Yang PR, Vandermeer B, Lindblad AJ. Opioid apply disorder in primary intendance: PEER umbrella systematic review of systematic reviews. Can Fam Phys. 2019;65(5):e194–206.

-

Kullmann S, Giel KE, Hu X, Bischoff SC, Teufel K, Thiel A, Zipfel South, Preissl H. Dumb inhibitory control in anorexia nervosa elicited by physical activeness stimuli. Soc Cognit Touch Neurosci. 2014;ix(seven):917–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nst070.

-

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: caption and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

-

Lingford-Hughes A, Welch South, Peters L, Nutt D. BAP updated guidelines: evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of substance abuse, harmful utilize, addiction and comorbidity: recommendations from BAP. J Psychopharmacol. 2012;26(7):899–952. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881112444324.

-

Luminet O, Bagby RM, Taylor GJ. Alexithymia: advances in research, theory, and clinical practice (2018).

-

Mills EJ, Wu P, Lockhart I, Thorlund 1000, Puhan One thousand, Ebbert JO. Comparisons of loftier-dose and combination nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, and bupropion for smoking cessation: a systematic review and multiple handling meta-analysis. Ann Med. 2012;44(half-dozen):588–97. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890.2012.705016.

-

Minhas M, Murphy CM, Balodis IM, Acuff SF, Buscemi J, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Multidimensional elements of impulsivity as shared and unique risk factors for food addiction and alcohol misuse. Ambition. 2021;159:105052. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105052

-

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke 1000, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew G, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(ane):1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-i.

-

Mph NAG, Kimberly Frost-Pineda P, Md MSG. Tobacco and psychiatric dual disorders. J Addict Dis. 2007; 26(sup1):5–12. https://doi.org/10.1300/J069v26S01_02

-

Munn-Chernoff MA, et al. Shared genetic risk between eating disorder- and substance-use-related phenotypes: bear witness from genome-broad association studies. Addict Biol. 2021;26(ane):e12880. https://doi.org/ten.1111/adb.12880.

-

Murray SB, Labuschagne Z, Le Grange D. Family unit and couples therapy for eating disorders, substance employ disorders, and addictions. In: Brewerton TD, Baker Dennis A, Brewerton TD, Baker Dennis A (eds) Eating disorders, addictions and substance use disorders: research, clinical and treatment perspectives, pp. 563–586 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-three-642-45378-6_26

-

Nøkleby H. Comorbid drug use disorders and eating disorders—a review of prevalence studies. Nordic Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;29(3):303–xiv. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10199-012-0024-9.

-

O'Hara CB, Campbell IC, Schmidt U. A reward-centred model of anorexia nervosa: a focussed narrative review of the neurological and psychophysiological literature. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;52:131–52.

-

Paslakis G, Kühn S, Schaubschläger A, Schieber M, Röder One thousand, Rauh Eastward, Erim Y. Explicit and implicit arroyo vs. abstention tendencies towards high vs. low calorie nutrient cues in patients with anorexia nervosa and healthy controls. Appetite. 2016;107:171–ix.

-

Peters ME, Taylor J, Lyketsos CG, Chisolm MS. Across the DSM: the perspectives of psychiatry approach to patients. Primary Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012. https://doi.org/x.4088/PCC.11m01233.

-

Press Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (2016).

-

Rachid F. Neurostimulation techniques in the treatment of nicotine dependence: a review. Am J Addic. 2016;25(6):436–51. https://doi.org/ten.1111/ajad.12405.

-

Rachid F. Neurostimulation techniques in the handling of cocaine dependence: a review of the literature. Addict Behav. 2018;76:145–55. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.004.

-

Root T, Pinheiro AP, Thornton L, Strober M, Fernandez-Aranda F, Brandt H, Crawford Due south, Fichter MM, Halmi KA, Johnson C, Kaplan AS, Klump KL, La Via One thousand, Mitchell J, Woodside DB, Rotondo A, Berrettini WH, Kaye WH, Bulik CM. Substance use disorders in women with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20670.

-

Rosager EV, Møller C, Sjögren G. Treatment studies with cannabinoids in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Eat Weight Disord EWD. 2021;26(2):407–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-020-00891-ten.

-

Schoemaker C, Smit F, Bijl RV, Vollebergh WAM. Bulimia nervosa following psychological and multiple child abuse: support for the cocky-medication hypothesis in a population-based cohort study. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32(four):381–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10102.

-

Schulte EM, Grilo CM, Gearhardt AN. Shared and unique mechanisms underlying binge eating disorder and addictive disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:125–39. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.cpr.2016.02.001.

-

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17. In StataCorp LLC (2021).

-

Striegel-Moore RH, Franko DL, Thompson D, Barton B, Schreiber GB, Daniels SR. Caffeine intake in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(2):162–v. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20216.

-

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-assay of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-assay Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. https://doi.org/x.1001/jama.283.fifteen.2008.

-

Umberg EN, Shader RI, Hsu LKG, Greenblatt DJ. From disordered eating to addiction: The "nutrient drug" in bulimia nervosa. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(3):376–89.

-

Val-Laillet D, Aarts East, Weber B, Ferrari Grand, Quaresima V, Stoeckel LE, Alonso-Alonso G, Audette Thousand, Malbert CH, Stice East. Neuroimaging and neuromodulation approaches to study eating behavior and prevent and treat eating disorders and obesity. Neuroimage Clin. 2015;8:one–31.

-

von Ranson KM, Farstad SM. Self-help approaches in the treatment of eating disorders, substance use disorders, and addictions. In: Brewerton TD,Baker Dennis A, Brewerton TD, Baker Dennis A (eds) Eating disorders, addictions and substance use disorders: research, clinical and treatment perspectives, pp. 587–608 (2014). https://doi.org/x.1007/978-3-642-45378-6_27

-

Walsh BT. The enigmatic persistence of anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(v):477–84.

-

Wierenga CE, Ely A, Bischoff-Grethe A, Bailer UF, Simmons AN, Kaye WH. Are extremes of consumption in eating disorders related to an contradistinct balance between reward and inhibition? Front Behav Neurosci. 2014;9(8):410.

-

Wilson GT, Shafran R. Eating disorders guidelines from Nice. Lancet. 2005;365(9453):79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17669-1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the O'Brien Constitute for Public Health & Mathison Middle for Mental Health Postdoctoral Scholarship, the Cumming Schoolhouse of Medicine Post-Doctoral Scholarship, and the Harley Hotchkiss – Samuel Weiss Postdoctoral Fellowship awarded to Daniel Devoe. Every bit well, the Cuthbertson & Fischer Chair in Pediatric Mental Health was awarded to Scott Patten. This work is besides supported past the Alberta Children's Infirmary Foundation and the Alberta Children's Hospital Enquiry Institute through Gina Dimitropoulos.

Funding

This work was supported past the O'Brien Found for Public Health & Mathison Centre for Mental Health Postdoctoral Scholarship, and the Cumming School of Medicine Mail service-Doctoral Scholarship awarded to Daniel Devoe.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

All authors edited and reviewed the manuscript. AA, JF, and Equally helped screen titles and abstracts, and full text. In addition, they extracted the data for tables, figures, and the meta-assay. TL conducted the risk of bias assessments. AB wrote the discussion and GP wrote the introduction. GD and SP oversaw both the clinical and methodological aspects of the newspaper. DD conducted the meta-analysis and wrote the methods and results sections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All authors give their consent for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This commodity is licensed under a Artistic Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in whatsoever medium or format, as long every bit you give appropriate credit to the original writer(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party fabric in this article are included in the article's Creative Eatables licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the textile. If material is not included in the article'due south Artistic Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/one.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this commodity

Cite this article

Devoe, D.J., Dimitropoulos, Grand., Anderson, A. et al. The prevalence of substance use disorders and substance utilize in anorexia nervosa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eat Disord ix, 161 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-021-00516-3

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s40337-021-00516-3

Keywords

- Anorexia nervosa

- Substance use disorders

- Substance use

- Eating disorders

- Comorbidity

- substance misuse

- drug corruption/dependence

Source: https://jeatdisord.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40337-021-00516-3

0 Response to "Co-morbidity of Eating Disorders and Substance Abuse Review of the Literature"

Enregistrer un commentaire